Sigh. I used the word ‘piss’. That’s bound to get this blog put on the naughty list. But it can’t be helped.

I’ve thought about the merits of Andres Serrano’s

Piss Christ, a photograph of a crucifix immersed in urine – Serrano’s own urine, in fact – for some time. The photo’s public prominence as a supposed example of liberal art gone wild was cemented by Senator Alphonse D'Amato, when he tore up a copy in the chambers of the U.S. Senate on May 18, 1989. But recent allusions to it in discussions of the publication of cartoons ridiculing Mohammed have prompted me to go public with what may be a difficult interpretation.

Fundamentally (alas, an adverb that carries too much freight these days), I think that

Piss Christ is a profound statement of Christian belief.

As an example of how it is perceived these days,

here is Anne Applebaum in the February 8 Washington Post. (A free subscription is required, and is only good for going back a few weeks; after that, they want cash from researchers.) Applebaum is listing the issues that she thinks have been pushed into public view by the cartoon controversy.

Hypocrisy of the cultural left. Dozens of American newspapers, including The Post, have stated that they won't reprint the cartoons because, in the words of one self-righteous editorial, they prefer to "refrain from gratuitous assaults on religious symbols." Fair enough -- but is this always true? An excellent domestic parallel is the fracas that followed the 1989 publication of "Piss Christ," a photograph of Christ on a crucifix submerged in a jar of urine. That picture -- a work of art that received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts -- led to congressional denunciations, protests and letter-writing campaigns.

At the time, many U.S. newspapers that refused last week to publish the Danish cartoons -- the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe (but apparently not The Post) -- did publish "Piss Christ." The photographer, Andres Serrano, enjoyed his 15 minutes of fame, even appearing in a New York Times fashion spread. The picture was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art and elsewhere. The moral: While we are nervous about gratuitously offending believers in distant, underdeveloped countries, we don't mind gratuitously offending believers at home.

Now I’m not interested right now in what debates went on at the

L. A. Times and the

Boston Globe. The question is whether

Piss Christ really is a bad-boy stunt intended solely to shock and offend, based on the adolescent presumption that the only good art is offensive. I suggest that there are three issues we need to investigate before we come to that assessment: (1) What are the purely aesthetic values of the work? (2) What significant meaning can we derive from the work? (3) What did the artist say about his intentions?

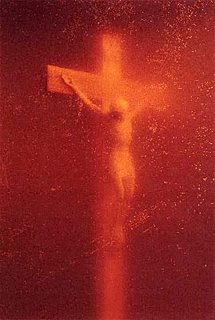

Aesthetic Quality: It is hard to appreciate the aesthetic impact of the photograph based on the sort of reproduction that we can post here. The original was large (60 inches by 40 inches), and glossy. The colors are saturated. If I didn’t know that the crucifix was in urine, I would be struck by the subtle golden hue of the crucifix seen against a red backdrop, the gauzy lack of focus that makes the image dreamlike, and the clear illumination from above, as if a single sunbeam had penetrated the storm to do homage. If there were no title, no information on how the image was produced, it would not be offensive. I doubt that I would find reason to revisit it the way I do major works, but I am glad to have seen it.

Significant Meaning: As I said above, the loss of focus suggests an event recalled at a distance, in memory or dream. That would be a reasonable, if not subtle, interpretation. But of course, the question is what meaning I derive from the fact that the golden glow comes from light filtering through urine?

The standard reaction is that it is disgusting. But why? Why is human urine disgusting? Clearly, we have strong cultural feelings against urine. I suppose many cultures do, although I’ve not researched it. But what do cultural stances have to do with the crucifix, which represents Christ’s sacrifice of himself for our sins? Not being repelled by urine is not a sin; urologists go to heaven too. And remember that Christ’s sacrifice is unlimited in its effect. Only those who turn from his offer are not supposed to be saved, and I gather that there is even debate about the permanence of their exclusion.

Think of this another way: Christ is willing to get into our beings no matter how repugnant our sins are. A carafe of urine – which is, after all, a natural product of our bodies – is not in the same category of vileness as sin. So why shouldn’t Christ be in the urine? Could there be some natural substance that could repel Christ? I can’t see how Christian doctrine could accept that.

So, the meaning I take from Serrano’s picture is that Christ is willing to go places where we aren’t. That his love transcends mundane concepts of ugliness. That the perfection of his sacrifice is far greater than any sacrifices we are willing to make, because it is extended everywhere and to everyone. This strikes me as a profound statement of Christian belief.

This sort of reaction is not just mine. For example, Leo Steinberg, in

The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and In Modern Oblivion, puts Serrano is a tradition of artists coping with the humanity of the incarnation. In a review in

oldSpeak, Joshua Anderson talks to Steinberg’s interpretation of the display of Christ’s genitalia, mostly in his baby pictures.

The emphasis on Christ’s sex, he writes, is meant to underscore his biblical humanity. Indeed, the paradoxical nature of Christ’s incarnation, his simultaneous divinity and humanity, has always existed in tension throughout Christian history… Displaying the masculinity of Christ was not the only way the artists instructed their audiences—Steinberg also shows paintings where the Christ Child stares out from the painting while nursing on the Madonna’s fully displayed breast, and others which focus on the circumcision of the infant Messiah. “Look,” the Renaissance artists seem to be saying to us, "consider the mystery and wonder of the Incarnation. See how the God-child’s body is like a man’s in every way. See how he suckles at his mother’s breast. See how he bawls when his blood is shed.”

In talking of Serrano’s message, Anderson says:

Serrano must have known that he was speaking a particular cultural language by mixing urine and Christ, one that was certainly intended to offend. So, although the righteous indignation of evangelicals is certainly justified, if one can look past the obvious mockery of Christ, there is, ironically, a subtle (and almost certainly unwitting) affirmation of the profoundly good news of the Incarnation… In contrast, Serrano’s mixture of Christ and urine is offensive, but not unbiblical, unless one holds to the Gnostic belief that Jesus was not completely human; indeed bodily functions are necessitated by concept of “the Word made flesh.”

In reality, the offensiveness of Piss Christ is due at least somewhat to the patently unbiblical nature of much current Christian art. That is, the submersion of Christ in a jar of urine is offensive to evangelicals at least partly because the humiliation and scandal of the Incarnation is, in practical terms, typically ignored in contemporary evangelical art.… Serrano provides an accurate understanding of the reality of the incarnate God; in his overt attempt at mockery, he establishes an important contrast to the candy-coated Christ found in most Christian bookstores.

Elissa, in

animated marginalia, makes a similar point:

Do we really believe that God became man and participated in all the disgusting, filthy, and thoroughly human stuff that makes up our daily existence? If so, if we do believe in a humiliated Christ, then Serrano's work can actually become convicting... even devotional. God Incarnate means God wallowing in our waste. What if this image was not an attack on our faith, but a challenge to those who claim it? What if we failed? What if we, too, have a history of refusing an insulted Savior?

And, in part of a very dense, deconstructist assessment in

Arts & Opinion, Damien Casey writes:

God's place is with the abject every bit as much as it is on the high altar of the cathedral. Yes, the crucifix as a triumphant symbol is a delicious irony in keeping with the spirit of the gospels. But that irony is lost when we forget its strong association with both ignominy and abjection. Then it merely becomes a sign of domination.

Serrano’s Intentions: I think that there is little or no direct evidence that Serrano produced

Piss Christ purely for its offensive effect. Serrano was not been very forthcoming about his motivation in producing the piece, preferring to let the discussion proceed without him. Eventually, though, he wrote an open letter to the NEA. In an excerpt published by animated marginalia, he says:

The photograph, and the title itself, are ambiguously provocative but certainly not blasphemous. Over the years, I have addressed religion regularly in my art. My Catholic upbringing informs this work which helps me to redefine and personalize my relationship with God. My use of such bodily fluids as blood and urine in this context is parallel to Catholicism's obsession with "the body and blood of Christ." It is precisely in the exploration and juxtaposition of the symbols from which Christianity draws it strength.

Amy Peterson, at Drexel University,

reported that the work was well within the context of Serrano’s other photos:

Some of his earlier works were quite abstract, involving the mixing of blood, milk, and urine. Serrano feels that these works are important because they were "going against the grain of photography in the sense that there's no perspective or spatial relationships. There's a flatness of color and material and subject matter."

As he progressed, he began to place objects he would find at flea markets in the bodily fluids. These photographs include Piss Mary, Piss Christ, and Piss Last Supper, in which statues of Mary, Christ, and Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper" were immersed in urine.

Serrano contends that his work Piss Chris would not have caused as much controversy if it weren't for the title. He claims that he meant no disrespect. However, he titled the piece in the same manner that he titled all of the works of the period: a description of the object seen as well as the liquid it was submerged in.

Bill Seeley, in a review in

Metapsychology of Cynthia Freeland’s

But Is It Art?, notes that

Serrano contends that the work was not intended to denounce religion, but rather to point to the manner in which contemporary culture is commercializing and cheapening Christian icons.

And finally, in an interview with Coco Fusco, in the Fall 1991 issue of

High Performance magazine, Serrano says:

My work has social implications, it functions in a social arena. In relation to the controversy over Piss Christ, I think the work was politicized by forces outside it, and as a result, some people expect to see something recognizably "political" in my work. I am still trying to do my work as I see fit, which I see as coming from a very personal point of view with broader implications.

So, dragging

Piss Christ into the debate over the Danish Mohammed cartoons, as a putative example of how it’s OK to bash Christian symbols in the liberal West, ignores the evidence of aesthetics, meaning, and intent, that it is legitimate art.